OPERATION PHANTOM FURY/AL-FAJR From the OCT 2010 files of SOF

I Fought in the Fiercest Urban Combat the US had fought since the Battle of Hue, Vietnam in 1968

By Jonathan Cuney

As I sit back and reflect on my time at war, no combat experience sticks out more clearly than the combat we saw on 12 December, 2004. The intense, daily fighting of the battle calmed down as we were re-clearing houses and mopping up the little resistance that remained. The press had lost interest by this point and moved on, leaving the events of this day mostly unreported. None of the Marines in my unit knew that on this day we would encounter the fiercest combat we were to face in Iraq.

The Battle of Fallujah was codenamed Operation Phantom Fury/Al-Fajr (the Dawn) and it played out very differently than other battles of the war. It was said to be the fiercest urban combat the US had fought since the Battle of Hue, Vietnam in 1968. It remains to this day the bloodiest battle of the War on Terror. Although tens of thousands of Americans cycle through the desert each year, some on multiple tours, only 15,000 saw action during the two battles that took place in Fallujah. Fallujah now has a mythical name to it that was built on the blood and sweat of those who served there between Jan 2004–March 2005. Because until December of 2004 Fallujah was enemy-occupied, the enemy had months to prepare defensive positions, place improvised explosive devices (IEDs), learn the terrain, and work on plans to disrupt our advances.

SIDE BY SIDE BLOCK BY BLOCK HOUSE BY HOUSE

I was an infantry corporal in 3rd Battalion, 5th Regiment (3/5), Kilo Company, 1st Marine Division. I had just gotten off of a two-year stint in security forces at the special weapons facility in Kings Bay, GA, and made my way to one of the US Marine Corps’ most decorated units. 3/5 was set to invade the city of Fallujah and the unit prepared stateside by training in urban warfare, close quarters battle (CQB), and security and stability operations. I was new to the unit and had to build a bond quickly as these men would be side by side with me fighting block by block, house by house, through a heavily populated and dense city. After we had dispensed thousands of rounds in marksmanship training, advanced CQB shooting, reaction drills, room clearing and urban patrolling, our time to deploy arrived.

I left several weeks ahead of my unit as I had volunteered to act as the non-commissioned officer in charge (NCOIC) of our unit’s gear shipment. I volunteered for this task as I felt I was long overdue to get boots on the ground and was eager to get into country. Security forces was a sit and wait-type duty, and with the images of the war raging on the nightly news and in the pages of magazines, I spent most of my time there biting my nails in eagerness to join the war effort. I didn’t waste my time, however, at this duty station, as I took advantage of every training opportunity presented to me in weapons, shooting and tactics. I began training on my own to learn Iraqi-dialect Arabic. It wasn’t until my arrival at Camp Pendleton, CA that the Fleet Marine Force taught me what being a Marine was all about.

A BRIDGE OVER THE EUPHRATES

In April of 2004, Blackwater Security contractors passing through Fallujah were caught in an ambush and killed; their bodies were burned and hung from a bridge over the Euphrates River. Several days after the killing of those contractors the US launched the first assault on Fallujah, codenamed Operation Vigilant Resolve. Operation Vigilant Resolve was launched on 4 April, 2004, and involved several thousand US Marines. It was a tough battle which cost the lives of 27 Coalition troops.

It ended on 1 May, 2004, with the withdrawal of the US Marines who were now drawing sharp criticism for the collateral damage being caused and the death of civilians within the city. They turned over control to the Fallujah Brigade, which was comprised of Iraqi Army and police officers, most of whom were sympathetic to the enemy. The enemy in Fallujah looked at it as a victory even though the Marines were outnumbered and still winning all the skirmishes. The enemy knew that the next time the Marines came, there wouldn’t be any stopping us, and they spent every second preparing the battle space. It was at the publishing of these news stories that I knew my unit was to be the one that ousted the insurgents from the last enemy-occupied city in Iraq.

Arriving in Iraq late at night on a C-130 from Germany loaded with gear was an experience in itself. The plane touched down after a plummeting dive to avoid lingering and becoming susceptible to anti-aircraft fire. After we touched down and our unit’s equipment was staged, I assigned my first guard of the rotation and we grabbed a tent and racked out for the night. I was up every two hours to do a guard rotation and stood several hours of guard myself in order to lighten the load of the other six Marines that I was given for the task. Several days later I got word from one of my men on post that we were ready to move our gear into Fallujah. Since we were just assigned as a security detail, we had been issued only two magazines of ammo in California, leaving my guys and me uneasy about a convoy down what was known as “IED alley.”

“Ok hold tight, I’ll be right back,” I told my guys, and moved off to God knows where to score God knows what. Asking around Al-Asad Airbase, I located the armory. It was in an old bunker left over from Saddam’s regime. “Hey Devil Dog how you doing,” I said to the armorer as I approached. “Been better,” he replied. “We all have. I need some shit; we are about to run a convoy op and me and my men are sitting with dicks in hand and only two mags of ammo left,” I said in a matter of fact tone. After being asked what I needed, I spent a little bit bullshitting with the armorer and smoking cigarettes and managed to snag two AT-4s, a couple of hand grenades, and a case of 5.56 ammo. When I returned my men looked at me in total awe, as they were expecting a few more mags of ammo and I had returned with a full combat load-out for all of us. If we got into some shit I didn’t want to be out-gunned, and since we were set to pass the city of Fallujah I figured “better safe than sorry.”

IEDS, BUNKERS, MACHINE GUNS AND SNIPER POSITIONS

At this point Fallujah was enemy-occupied, with no US presence in it since April. The enemy had spent their time planting IEDs, digging bunkers, setting up machine gun and sniper positions, launching harassing operations on our forces outside the city and training themselves for the US assault they knew was imminent. The US Marines that had withdrawn previously set up cordon positions around the city, in which they observed the highways around the city and from which they launched random surprise checkpoints and patrols. Our convoy should have taken an hour, but since the US couldn’t take the risk of driving trucks over Fallujah’s bridges (which were giant choke points) and through a hostile city, the convoy took nearly three hours as we had to go around. Despite all the preparation the convoy was mostly uneventful minus the few IEDs we encountered. When we arrived at Camp Baharia outside of Fallujah, however, it was a different story.

As we were less than a mile from Fallujah’s city center and they undoubtedly noticed the massive convoy slipping in the back gate, mortars began raining down on our positions. We took cover under concrete bunkers which were placed around the base to deal with just such attacks. I couldn’t help but to smile; I was getting my cherry popped for the first time—I just got mortared. After several days of meeting the gents from the unit we were to replace, 3/5 showed up and we were re-attached with our original companies. We then went out to man positions around Fallujah. I was over eager to get some, always going out on patrols, searching homes and vehicles around the outskirts of the city and trying to establish intelligence sources on activities inside the city.

FIGHT OR GET THE HELL OUT

By this point I had a decent grasp of Iraqi Arabic, as I had been studying it on and off for the past few years and in every encounter I had with an Iraqi I attempted to put it to use, helping me further my language ability. After months of counterinsurgency operations and light skirmishes we got our green light to invade the city. The US Army replaced us at our cordon positions, blocked the roads into the city and searched everyone coming out, and we returned to base to train one last time prior to the assault. Leaflets were dropped and word was spread to Fallujah’s 450,000 residents, unless you want to fight, get the hell out. It was like a mass exodus from the city as the residents packed up and left.

The largest terrain model I have ever seen in my life was constructed on the base to give us our battle plans; we walked through the steps of the assault block by block and unit by unit. We rehearsed dismounting and mounting vehicles, did a final battlesight zero of our weapon systems, cleaned them, and loaded up our AMTRACs for the short ride into Fallujah. We took the least expected route and managed to avoid fire the entire way. We staged in a canyon in the desert right outside the city while Marine Corps Recon raided an enemy cement factory that was being used as a listening post/observation post by the enemy. We didn’t hear a shot, but it was neutralized. We waited all night in the cold desert until at 0430 we were told to get ready to attack at dawn. We loaded up the armored tracks and headed into the city at around 0500. Our objective was to take an apartment complex that would be used as our battalion HQ. It consisted of eight five-story buildings, a mosque and a school, and was located about 250 yards from Fallujah’s northwest corner.

We took fire immediately upon pulling up as mortars and rockets greeted the troops running to secure the buildings. We blew doors in, bashed them down, and evicted the tenants into busses and trucks to be sent outside of the battle zone. We placed snipers and M2HBs (Browning .50 caliber machine guns) on the roof to keep the enemy at bay while combat engineers rolled in with armored bulldozers and pushed up the sand all around our perimeter and ran concertina wire around it. Trucks full of sandbags we had spent previous weeks digging showed up and we began to fortify. By day’s end we had absorbed sniper, rocket and mortar fire constantly but the fortification was complete. That night India Company 3/5 would blow a crater into the railroad tracks and make a breach into Fallujah followed closely by everyone else across the entire north end of the city. Our unit hit the Jolan district first and encountered resistance as the entire advancing force was on a long line across the city’s north and cleared south, ensuring no one slipped through the cracks.

INSURGENT’S COUNTERATTACK ON FALLUJAH

Day by day, block by block we fought through the city and searched every house on the blocks we cleared. Some were empty, some had civilians, and others had enemies. We lost several good men during this initial thrust and all felt their losses. After the battle was said and done we began the task of re-clearing our newly claimed piece of real estate.

It was reported by the Army that on 11 December a large group of men entered the city from the east, and they were unable to engage them all. This was the Iraqi insurgency’s counterattack on Fallujah and it was never published or reported, as the media only covered the first days of the battle before losing steam and moving elsewhere. On 12 December my platoon was sent to patrol a region in which some insurgents were thought to be taking refuge. As we searched houses all day we found nothing. No signs of people, no fresh anything. Toward the evening we began heading back to our hasty fortified position, which was in a school compound on Fallujah’s central eastern side. The order came down to move into the blocks directly adjacent to our patrol base and search the homes before returning for the evening. I spent 12 December leading an Iraqi patrol on clearing operations through the city as their adviser; we made entrance into the first house on the block and cleared it. Once it was deemed all clear and we were about to head back to base, I heard the shots.

The Iraqi LT came in and told me the Marines were encountering enemy in the next house. I told the LT to stay put and keep his men on alert and I took off to join my Marines in combat. As I got to the front gate of the house there were Marines all over the place, bleeding, wounded, some dead. I charged into the courtyard and took rifle fire from someplace I couldn’t identify. I made it to the walls of the house and saw my squad automatic weapon (SAW) gunner leaning against a wall getting some. As I made my way to him I told him to cover me to the side of the house as I attempted to get around the back. I figured once around back I could slip in and wreak havoc while the insurgents were concentrating forward. When I reached the alley I saw the slumping body of my friend, my squad leader, and my mentor in the Marine Corps Sergeant Jeffery Kirk.

“I think its SGT Kirk,” I said as brass from the SAW was spitting everywhere and impacts were chipping the walls around us to shit. As much as I wanted to retrieve his body, I knew that the alley was covered by fire and if I made my way down it I would be next on the chopping block, so I moved toward the front and got men to help me retrieve the body. After we got him out of the alley I was stunned. I had the deepest loyalty and respect for that man. I would have followed him to hell and back; every man in my unit felt the same way. I was stunned at what I was seeing. There were men bleeding, crawling, screaming, and some dead, they were everywhere. I felt drunk, like I was floating in a nightmare. The entire block was embroiled in a battle as every house on the block was filled with insurgents. Reaction forces started showing up and 3/5 K Marines were now mixed with other Marines they didn’t know as casualties started mounting. About four houses were filled with enemy and people were dropping to sniper fire, rocket fire, grenades, and machine gun fire everywhere.

I COULD FEEL DEATH IN THE AIR

A tactic we learned in Fallujah used by the insurgency was to leave the first house on a block empty by the enemy. This was so that as Coalition troops made entry onto a new block, they would feel comfortable that things were safe; once they got deeper into the block insurgents would attack. This block would be the perfect example of that tactic as we encountered dozens of enemy foreign fighters hunkered in for a fight and ready to die.

I grabbed 2 PFCs from the reaction force I didn’t recognize and told them to come with me. Everyone seemed to be on litter duty as there was so many wounded and dead. As I made entrance into the house with two Marines on my heels, the hair was standing on the back of my neck and goose bumps were raised on my entire body. I could feel the death in the air. We slowly cleared the downstairs of the house and it was then that I bumped into a familiar face, my friend and squad mate Corporal Robbie Goodson. As we nodded in acknowledgement to each other upon his entrance into the house, we began hearing the battle cries of our enemy upstairs. “Allah Akbar” they shouted.

“ANI-CHECK BIN GHABBA” I shouted in reply. This is roughly translated as “I’m going to f–k you, you sons of whores.” The shouts ceased and a few grenades came down the stairs. We remained silent, weapons trained on the stairs. An AK popped over the rail and let off a burst but there wasn’t enough target for us to hit so we remained covered. Shortly after that, as Cpl Goodson and I were scheming on how we were going to kill the SOBs upstairs, some personnel other-than-grunt (POG) cowboy came running in like he was Rambo and tried to take charge. “Come on, lets go” he said, running onto the stairs. “Hey, they got it covered by fire,” I said just as he got his legs mowed by a burst of AK fire. “Cover me,” I said as I moved up the stairs to make it to the screaming idiot. As I got to the platform and got the Marine turned around to pull back down the stairs, a grenade landed on the platform—a Soviet RGD-5.

“GRENADE!!!!”

I’ll never forget staring at it, shitting in my pants. I immediately pushed the wounded Marine down the stairs and as he began rolling I shouted “GRENADE” and started moving up the stairs to avoid a pile up on the staircase below. As I ran up the stairs a mujahedeen hung his AK out the door and let off a burst of AK fire, shredding the wall to my right, chipping the concrete into the neck of my body armor. I fell backwards and rolled down the stairs just in time to get my leg and foot hit by the exploding grenade. I caught hot shrapnel to my left foot and my legs; luckily my boot and my knee pads helped absorb a lot of the blast. I was disorientated and the next thing I remember was linking back up with Cpl Goodson. “Holy shit, I love you, ” I told him. In Marine jargon, at that time, it meant thanks and he understood. We laughed about it after all was said and done.

At this point the two PFCs I had snagged had grabbed the wounded Marine and taken him to the corpsman, so CPL Goodson and I were in the house alone. As we were attempting to regroup and work out a plan to get back up there and take the enemy out, a Marine came in and said air support was en route. We nodded in understanding, took a few shots, launched a few M203 grenades, tossed a hand grenade or two and made our withdrawal. Outside the house I will never forget the scene. American bodies lying in a row being loaded into HMMWVs, dozens of injured being loaded into AMTRACs, and blood on everyone. We took refuge in the row of scattered houses across the street and awaited air support.

After several 500lb bombs were dropped, the houses on that block still remained standing, though damaged. As we would learn the next morning, the men in those houses were still alive. Snipers and tanks spent the night shelling and killing anything that moved on that block and early the next morning our mortars began raining down. Machine gunners opened fire to prep for our assault. Within minutes we had already taken more casualties and spent almost the entire second day fighting on that block. The enemy had fortified this area and was not budging. Several more men were wounded and killed the second day of this battle. After finally clearing the block we moved on, and the remaining tour calmed down a lot.

DEATH AND VIOLENCE ON EPIC SCALES

We did patrols around the city; when residents came back we had a huge presence, manned checkpoints, and conducted counterinsurgency operations. The haunting memories of 12 December, 2004 would live with all of the men of 3/5 Kilo Company forever. I was always chasing medals, glory, fame, and on the day I had my chance, I kept quiet. How, in the face of so much loss, could I stand up and ask for acknowledgement or recognition? So many good men died and were permanently wounded. They are true heroes and my glory and fame came at the honor of having met them and served with them. I wasn’t even awarded a Purple Heart until shrapnel was discovered still in my leg at a VA clinic several years later.

The lessons we learned in Fallujah taught us all about the dangers of urban warfare first hand. SWAT teams the nation around may only raid 100 houses a year x 20 years. That’s 2,000 houses in a lifetime for a busy team and maybe one would never encounter an officer involved shooting in that entire time. The Marines in Fallujah cleared 10,000 houses plus and encountered grenades, machineguns, snipers, booby traps, and suicidal terrorist on a regular basis. We became instant experts in urban warfare and close quarters battle. We learned how to avoid IEDs you couldn’t even see, as they were buried in the sidewalk; we learned how to sense snipers three blocks away and through two buildings. We fought insurgents who injected AIDS and hepatitis C into their blood steam in an attempt to kill us if their bullets couldn’t, and saw death and violence on epic scales. We developed crude weapons out of what we had, such as water bottles refilled with gasoline, gelled, and tied by a flex cuff to a flash bang. When the pin was pulled and the bottle released, it made for a nasty surprise to those occupying bunkered rooms and fighting positions. As simple as this device was, it saved countless American lives.

Since I left the Marine Corps in 2005, I have worked as a private military contractor conducting asset recovery and securing property post-Hurricane Katrina in New Orleans, recruited British SAS and French Foreign Legionnaires for work in Africa, did executive protection in the Caribbean and Central America, and rescued a trapped American in a hostile Asian nation. I earned my Bachelor’s Degree in Military Intelligence Studies from American Military University; obtained certificates in humanitarian logistics, peacekeeping, and post conflict affairs from the Peace Operations Training Institute; became a certified armorer for Glock pistols; took medical courses at the American Red Cross; and am about to start my Master’s program in September. Of all that I have done in my life, no moments have yet to stand up to my memories of 12 December, 2004.

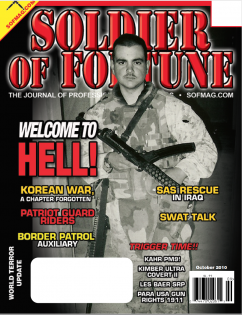

Soldier of Fortune Magazine The Journal of Professional Adventurers

Soldier of Fortune Magazine The Journal of Professional Adventurers