by Martin Kufus

Editor’s note: This is an excerpt from Plow the Dirt but Watch the Sky, a memoir by Martin Kufus, a former editor at Soldier of Fortune. This chapter shows Martin’s experience at the Special Forces SERE Instructor Qualification Course, where he encountered the legendary Col. Nick Rowe – who was assassinated on April 21, 1989. The final line in this excerpt will make your screen go blurry. ~SKK

“S is for Survival”

The dark green UH-1 “Huey” helicopter hovering above us was a later model than those flown in South Vietnam. It had hopped over from Fort Bragg west to Camp Mackall, the small Special Forces-training base in rural North Carolina. We were on Day 10 of the 26-day SERE Instructor Qualification Course in August 1985. And this day was going to be fun. Preceded by classroom instruction and a safety briefing, our ‘Helicopter Recovery Operations’ training would be hands on and knees in the breeze.

“Everybody ready?” yelled Nelson, a sergeant first class from a Ranger battalion and the ranking member of our six-student team.

Harnessed and ready for our ride, we all signaled thumbs up: Owens, an Air Force pararescue jumper (PJ); Vandersteen and Gann, two SF A-Team operators; Jones, a pathfinder from the 82nd Airborne Division; and me, a Russian linguist and “buck sergeant” soon leaving a signal-intelligence (SIGINT) team in the 5th SF group at Fort Bragg for an Army–National Security Agency station overseas.

Although the other services had their own SERE programs, there was intermingling at Camp Mackall. Besides the PJ, our all-male class also had several Air Force combat controllers and one force-recon Marine.

The six students before us had unhooked and stepped away from the SPIE rig of nylon tethers and metal buckles connected to a thick rope hanging from the helicopter. The ‘Special Patrolling Insertion/Extraction’ technique was developed by US Marine Force Reconnaissance for its teams’ quick entry into and/or removal from Vietnam’s jungles without requiring a helicopter landing.

READ MORE from Martin Kufus: ‘G is For Gonzo’: A Slice From an Editor’s Life at Soldier of Fortune

Bareheaded, we hustled over to the SPIE rig, arrayed on the ground, and hooked our carabiners onto our assigned tethers. Then we stood apart, arms raised, for a quick safety inspection by SERE cadre members. That done, one of the instructors looked up at the helicopter hovering at 40–50 feet. Through the noise and dirt cloud in the rotor’s down blast he hand-signaled the Army crew chief crouching in the aircraft’s open doorway. The 2-inch-thick cargo rope grew taut as the bird rose.

The two guys standing in front of my partner and me were now hanging above us. Then, my jungle boots left the Carolina dirt and my partner and I were suspended above the last two team members. My partner and I wrapped an arm around each other’s torso and a leg around the other’s leg, then extended our free arms and legs, skydiver fashion. The pilot throttled up the rpm’s. Seconds later we dangled perhaps 300 feet above the green countryside, and then over a small lake, in a wide racetrack around Camp Mackall.

All six of us were trained as paratroopers; zooming along a lethal distance above the ground was no reason to freak out. We whooped and hollered with delight as we flew below the noisy Huey.

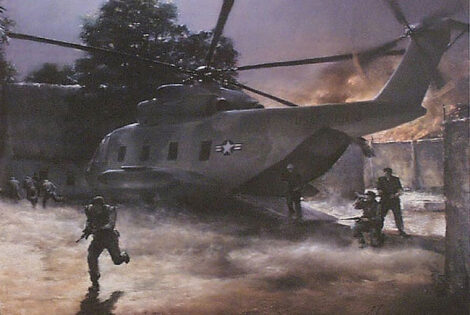

Our next round of helicopter recovery training had an interservice flavor but wasn’t quite as dramatic. An Air Force HH-53 ‘Jolly Green Giant’ combat search-and-rescue helicopter descended outside Mackall two hours later. The Sikorsky was much larger than the Army Huey we’d used earlier. Its single main rotor created a deafening clatter. Our class of 24 students took individual turns at the LZ strapping onto a jungle extractor rescue seat to be hauled 50–60 feet up a metal cable and then back down.

After we all had gone up and down and the Jolly Green departed, our class walked back into the compound. We saw a small group of cadre members standing outside the SERE “head shed” (command and admin building).

At the center of the group, listening, nodding, and occasionally speaking, stood a middle-aged man of medium build, maybe 5 foot 8 inches tall, with short dark hair and glasses. If he hadn’t been wearing jungle fatigues and boots and a green beret, he could’ve been mistaken for a college professor of engineering which, actually, was what his West Point degree was in. Colonel Nick Rowe definitely did not look like any “Rambo.” Rather, he was the real deal who had killed enemy soldiers, narrowly avoided violent death, suffered unimaginably in captivity, and escaped to tell about it. Rumor had it the Communist bloc had put a price on his head.

With Vietnam behind him, the former POW returned to active duty in 1981 at Fort Bragg to create a comprehensive SERE program for the Army. The Special Forces Qualification Course, which I unsuccessfully tried to get into, already had a SERE component of training. Ranger school, at Fort Benning, Georgia, had a few SERE classes, too.

In much of the rest of the Army, though, this broad topic was dealt with, if at all, as a hodge-podge of in-unit classes usually read from field manuals on the Geneva Convention, Code of Conduct for US troops, and survival techniques. Such training would become known as Level-A SERE; the instructor-qualification course at Camp Mackall was Level B. And, beginning soon, in early 1986 we were told, there would be a Level C course of 18 days. It would have classes, a field training exercise ( FTX) emphasizing evasion, and a scripted-in capture followed by days of confinement in a mock Communist POW camp.

That camp was being built somewhere on Fort Bragg, we were told. It would be staffed by trained role players who would ensure the students were roughed up a little bit, deprived of sleep and food, grilled around the clock with questions, and badgered with phony indoctrination propaganda. Priority for class slots would go to high-risk units such as Delta Force, the ‘Night Stalkers’ aviation unit, Special Forces, and the Rangers. Although I was enough of a glutton for punishment to have applied for Level C had I stayed at Fort Bragg, Level B would be my last hoorah there, as my re-enlistment assignment was a strategic SIGINT station in West Germany. So, this course would have to be suffice for the foreseeable future, anyway. It was plenty.

Colonel Rowe and his cadre packed a lot into 26 days.

Nick Rowe.

Information came at us like water from a fire hose: water procurement and storage; food procurement including animal snares and traps; first aid and primitive survival medicine (e.g., splinting a buddy’s broken limb with a stick and vines or strips of cloth, or maggot therapy to excise dead flesh from a pre-gangrenous wound); field-expedient shelters and tools; cross-cultural communication to befriend locals; evasion techniques to throw off pursuers and, if necessary, kill their tracking dogs; and, navigation without a compass. There were even classes on how to teach these topics.

The outdoors was our classroom, too. The SF instructors showed us animal snares and traps they’d built and set, then put us to work on our own using sticks, wire, and string. These devices would work on mice, rats, rabbits, squirrels, and maybe birds. Then, there is snake meat—lean, white, and nutritious. Its procurement can be dangerous.

We gathered in a circle facing one of the SERE instructors, an SF master sergeant, who stood on the grass beside a box made of plywood and thick wire mesh. He unhooked a latch and opened a small door on the box, then stepped back. Out crawled a thick-bodied, copper-and-tan snake, maybe 3 feet long with a triangle-shaped head. Its camouflage pattern would’ve blended in perfectly among fallen leaves, pine needles, and cones. The snake’s tongue repeatedly flicked the air for scent. It perceived it was surrounded by humans. It stopped crawling and began to coil.

“This is a fully grown, adult male copperhead,” the instructor said.

A fully envenomed bite from this heat-seeking viper probably wouldn’t kill any of us, he continued, but it would hurt like hell, incapacitate, and require medical attention. We had covered that in first aid and survival medicine. The instructor stepped forward holding an aluminum pole with a hook on the end. The snake assumed an even tighter coil, head raised, and ready to strike. Unlike a rattlesnake, with its noisemaker usually signaling a warning, the copperhead was silent.

“Watch carefully,” the instructor commanded. He slowly moved the end of the pole toward the snake. At a range of a foot or two, the copperhead struck. And again—the snake struck at the pole. The instructor circled around the snake at a distance of 4–5 feet. The copperhead shifted its dramatic pose to follow the human’s movement. Joe No-shoulders didn’t strike with his whole body length—only about half, I estimated. That’s his strike range.

Don’t get within the strike range!

Improvisation and making do were emphasized. After a class on field-expedient survival tools/weapons, each of us was given a flat rectangle of rusty metal measuring perhaps 1 × 4 inches. We were instructed to affix it somehow to a piece of wood—we could use tree sap, a “glue” when it hardened—then sharpen it with a flat rock to make a cutting tool to take on the FTX in lieu of any knives.

For inspiration, instructors let us examine a dozen shanks and homemade knives that had been confiscated from inmates at a North Carolina prison and donated to the SERE course. Our ingenuity or attempts at it did not stop there as we prepared for our six-day field training exercise in the nearby Uwharrie National Forest.

In the exercise’s first three days, the evasion portion, each of our student teams would walk miles at night by compass and map, hide by day, and evade “capture” by patrols from the 82nd Airborne. During the FTX we would haul our meager supplies—which did not include any “meals, ready to eat” (MREs)—in homemade load-bearing gear. Our Air Force PJ, Owens, was trained as an emergency medical technician; he would carry the team’s first-aid kit. I knew I would likely carry the PRC-77 field radio, which was about the weight and bulk of a large truck battery, for most of the evasion-phase movement. Signal intelligence meant signal which meant radioman—I learned that a year earlier in Ranger school.

So, I set to work on a wood-framed rucksack I hoped would be sturdy enough. A wire saw, a nail, and my homemade knife were my tools. The components were sawed pieces of a green (not dead) tree limb as the backpack’s frame, wood sap as glue, a few feet of thin wire, and an unlimited supply of the invasive kudzu vine with which to fashion a cargo basket and shoulder straps.

In the FTX’s last three days, each student was assigned a hide site near the Little Uwharrie River. He would perform a list of graded tasks—constructing animal snares that actually would work, building an improvised shelter, preparing a small campfire, creating a low-tech weapon from materials at hand, and penciling “survival diary” entries into a small notebook—while avoiding discovery by foot patrols from the 82nd. Food would be whatever the student could catch or find (e.g., earthworms).

Colonel Rowe’s hand-picked SERE cadre from Fort Bragg mostly comprised older SF soldiers and a few retired Vietnam veterans.

There were guest instructors, too. One was a Judge Advocate General (JAG) lawyer, a major from Fort Bragg, who lectured on the Geneva Convention and standards of conduct regarding surrender, treatment as a POW, and escape. In another class, a warrant officer in counterintelligence described the forms of torture Communist interrogators had used on American POWs during both the Korean and Vietnam wars.

This topic drifted into the classified realm. Indeed, Col. Rowe’s 2 ½-hour ‘“Seminar on Communism”’ on Day 12 was the reason why students had to have at least a Secret clearance.

At some point during captivity, Col. Rowe said in his lecture, an American POW could face very hard decisions under coercion to turn against his country.

“Is what I believe in worth my suffering or death?” Col. Rowe said rhetorically. “Is the US political system worth preserving?”

You could’ve heard a pin drop.

Around the classroom, heads nodded. The ex-POW added that many Americans—including some in the military—frankly do not know much about their own country’s history, government, and political process. And a POW’s ignorance would be exploited for Communist indoctrination and propaganda.

Army SGT Martin Kufus, 1984.

Americans often were poorly prepared in other areas, too. At that time, unarmed-combative training across the Army was spotty. Colonel Rowe valued it, though. One of the guest instructors was a civilian, a heavy-set guy who wore a red martial arts gi and sneakers. The patch on his jacket indicated a Chinese fighting system. He was there to teach a hand-to-hand combat technique Col. Rowe was especially keen on: “the whip.” It did not require brute strength, which a malnourished POW probably wouldn’t have anyway while attempting to escape and evade.

This backhand strike led with the knuckles of the open hand; upon their contact with an opponent’s face, throat, or temple, the four fingers then snapped forward to multiply the impact—fast like a whip. It was a stunning, not killing, strike that had to be followed with another blow or two, we were instructed.

On another long day, we spent hours paired off in Mackall’s hand-to-hand pit of sand practicing “sentry take-out” techniques demonstrated by the instructors. Then, we took it to the woods—at night.

Divided among four lanes, we rotated in the roles of enemy sentry, standing on the edge of the woods looking away, and evader, approaching from 10–15 yards back in the trees. The silent attack in partial moonlight required a slow approach from behind using footwork we’d learned and practiced by day on dry twigs, leaves, and pine needles.

“Don’t stare at the back of his head; he’ll sense it,” an instructor added.

At arm’s length, the evader struck. One hand covered the sentry’s mouth to stifle a yell as the other went for the throat. In a whirl, a pivot step and hip roll put the sentry face down onto the ground. Then, the attacker dropped a knee onto the other student’s back and simulated ripping his throat out with a claw hand. An instructor stood close by, watching each pair of students.

Sometimes, dissatisfied, he ordered a do-over. Thud … thud … thud … We also stayed up late negotiating obstacle courses at Camp Mackall.

Fifty yards of barbed wire and ground-flare trip wires awaited us. Here and there in the field was a partial coil of razor wire. Each evasion team had to belly-crawl a single file under or around the obstacles. There was a little moonlight. The team’s lead man clutched a long blade of grass and probed in front of him for trip wires. When he found one, he carefully hung a white sheet of MRE toilet paper on it to alert the men behind him. The last man removed the marker.

Intermittently, the cadre launched parachute flares. Everyone froze until the eerie, bright light hit the ground and burned out.

We smeared field-expedient camo paint (mud) on our faces, and waited for our team’s turn to go.

READ MORE: Col. Nick Rowe: Long-Ago Conversations With a Special Forces Legend

In the light of the moon and aerial flares, two figures approached. One was Col. Rowe. The other was a taller, heavily built man also dressed in jungle fatigues and wearing a green beret.

In an Eastern European accent, the big man asked each student on our team what he did and which unit he came from. When he got to me, I said, “I’m a Russian linguist in 5th group, Sergeant Major.”

He smiled slightly, eyes narrowing. “Так, вы говорите по-русски?” he said with a perfect accent. So, you speak Russian?

“Да. Я говорю немного по-русски,” I replied with a not-so-perfect accent. Yes. I speak some Russian.

He glanced at Col. Rowe, who apparently was enjoying this little interrogation, and then back at me. “Где же вы научились русскому языку?” he continued. Where then did you learn Russian? My five teammates observed silently, perhaps hearing the “threat” language spoken live for the first time.

“Я учил русский язык сорок-семь недель в военном институте иностранных языков в Монтерей, Калифорнии,” I replied. I studied the Russian language 47 weeks at the military institute of foreign languages in Monterey, California.

“Очень хорошо,” the sergeant major replied, nodding. Very good.

I noticed Col. Rowe was grinning broadly. For a low-ranking, inexperienced SF nobody like me, it was an excellent moment. And then, the moment ended. It was our evasion team’s turn to get down in the dirt and slither like snakes.

Later, I figured out I had been quizzed in Russian by another Special Forces living legend: Vladimir Jakovenko, a Ukrainian immigrant who served in the US Army in Vietnam, most notably as a “Son Tay raider.”

~ ~ ~

On a warm Appalachian afternoon, I sat beside my future ex-wife on the front porch of a small house we rented on the outskirts of Athens, Ohio. It was April 1989. The SERE course was not quite four years behind me, and I had left the Army 11 months earlier with a bum knee.

I leafed through a New York Times I’d bought at a bookstore near the campus of Ohio University, where I was working on a master’s degree in journalism. The day before, I’d heard on TV news that a US Army officer, a counterinsurgency advisor, had been shot dead in the Philippines by a carload of gunmen that pulled alongside him as he was being driven to work. On this day, I must’ve overlooked that story in the front pages of the Times. I turned to its obituary section.

Instantly, I recognized the face in a black-and-white, head-and-shoulders photo, then took in the headline. I read the 11-paragraph obit, blinked away a tear, and looked up from the paper.

“They got Nick Rowe.”

Soldier of Fortune Magazine The Journal of Professional Adventurers

Soldier of Fortune Magazine The Journal of Professional Adventurers